Presenting the Project in Lund

“Nordic Media Histories” was the topic of the three-day symposium at Lund University, 12-14 August 2020, to which I was invited to give one of two keynote presentations. (The other one was by USC historian Nick Cull, in whose company I was quite pleased to find myself.) But we were told that there was no need to focus on the Nordic countries; we should, rather, offer broad perspectives that could be of interest for media historians focusing on matters of propaganda and information in the post-1945 period.

Seizing the moment to get busy with our INIDUN project, I presented a paper entitled “Transnational Media Histories of (or rather, through) UNESCO: An International and Digital Approach.” Here, after presenting the project over all (and trying, more or less successfully, I think, to show its relevance to the context of the symposium), I discussed the results of my recent exploration of one part of our UNESCO text corpus: the organization’s standard-setting instruments, or SSIs. These are the conventions, resolutions, and declarations that UNESCO has adopted, some 82 in all (from the 1945 constitution that founded UNESCO to the “Recommendation on Open Educational Resources” of November 2019). Assembled as a text corpus, they amount to 286,235 words. By way of preliminary exploration, I fed this corpus into the online text analysis tool Voyant, using this to identify word trends, collocates, and more.

One simple but striking finding was this: UNESCO would seem to have been an organization with a deep and long-standing concern with matters pertaining to the media. After all, UNESCO’s founding constitution explains that, to realize its purpose, the organization will “Collaborate in the work of advancing the mutual knowledge and understanding of peoples, through all means of mass communication and to that end recommend such international agreements as may be necessary to promote the free flow of ideas by word and image.”

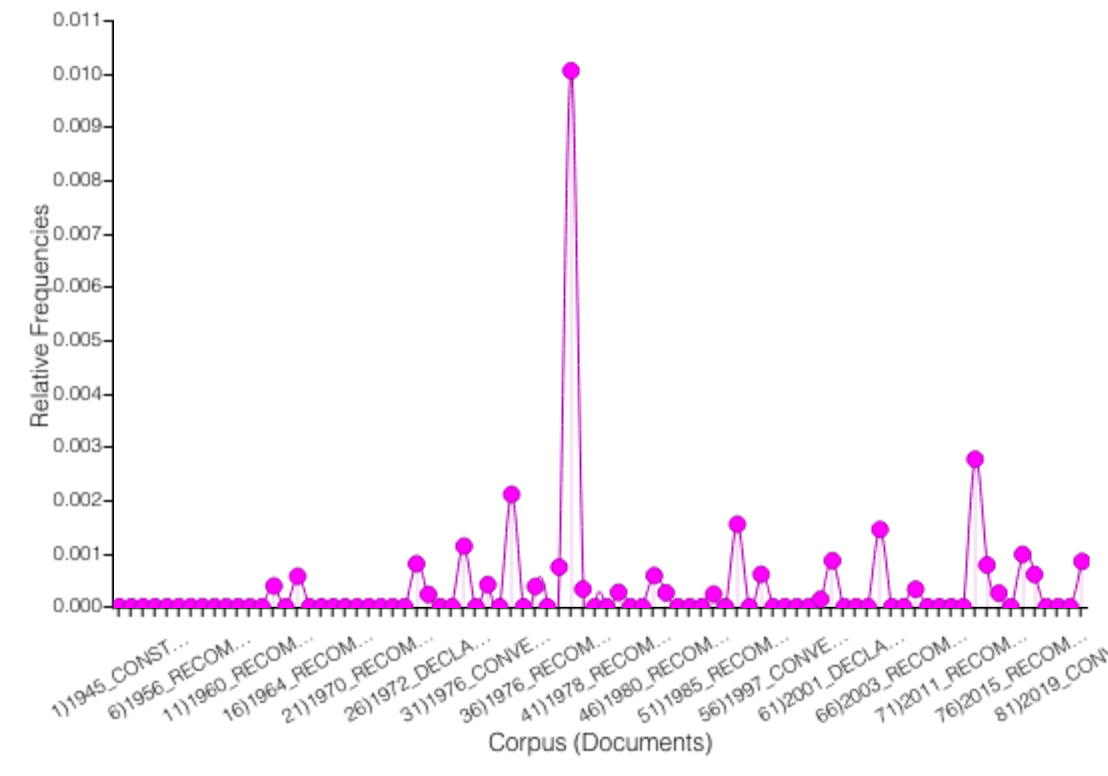

So, how often have “media” in fact been an explicit focus of UNESCO’s SSIs? As you can see, not often at all.

With one major exception: the spike in the middle is the Mass Media Declaration (actually called the Declaration on Fundamental Principles concerning the Contribution of the Mass Media to Strengthening Peace and International Understanding, to the Promotion of Human Rights and to Countering Racialism, Apartheid and Incitement to War) adopted by UNESCO’s General Conference in November 1978.

Scholars are aware of this Declaration, of course, and it’s no surprise to find a spike in that word’s use at that point. But for us, this is interesting: it seemed reasonable to think that “media” was a natural field for UNESCO, yet in fact there was, apparently, only one moment in UNESCO’s history when media was a major issue — or, at least, an issue major enough to lead to the adoption of an SSI. It is striking, too, that “media” was not a significant term before or after that date. (The later small spike is a 2015 declaration on sports, that invites “the media,” among other social forces, to promote the value of physical education and exercise.)

We know that the Mass Media Declaration reflected the ideas and goals of the controversial effort to create a “New World Information and Communications Order” – an effort that led the USA and UK to withdraw from UNESCO altogether. Could it be that what we see in this graph is a story: in which an effort to pull the media to the heart of UNESCO’s concerns was followed by silence on that issue when the effort was defeated?

Stay tuned…!